This post may contain affiliate links and ads in which we may earn a small percentage of purchases.

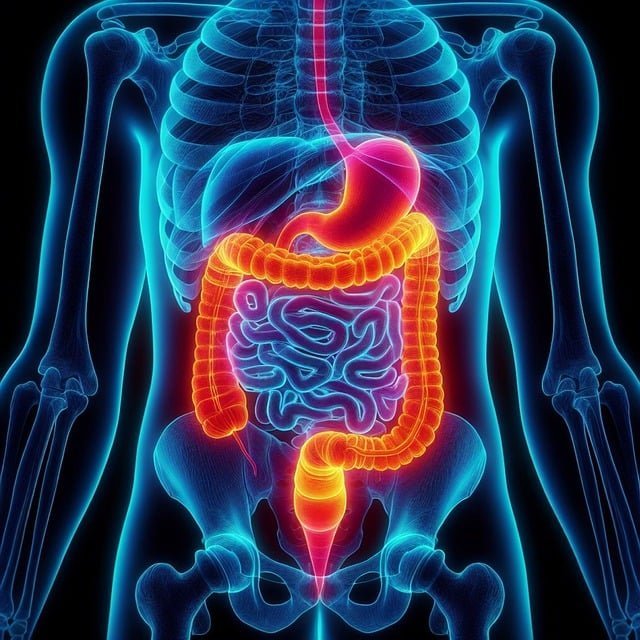

How do we digest food? The food we eat everyday? The food we shove down our mouths because we’re going to be late, we need to rush, etc? Can we give a little thanks to our Digestive System please!

The Beginning Of The Digestive System

You may know this already, or not, but what is digestion, anyways?

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), it is “The process your body uses to break down food into nutrients that your body uses for energy, growth, and cell repair.”1

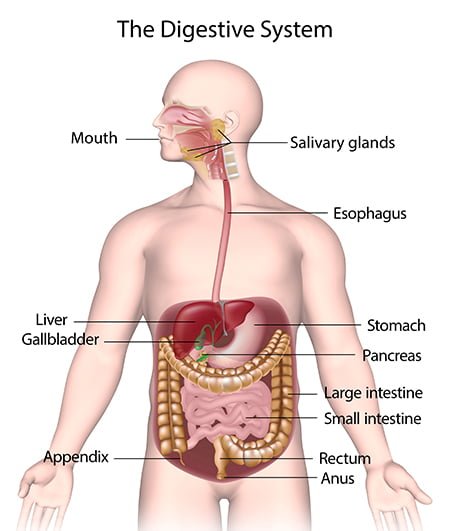

It all starts in the mouth where food is chewed and mixed with saliva. This forms the bolus, which is then swallowed. Once in the stomach, the bolus is further broken down by stomach acids, turning into a semi-fluid mixture called chyme.

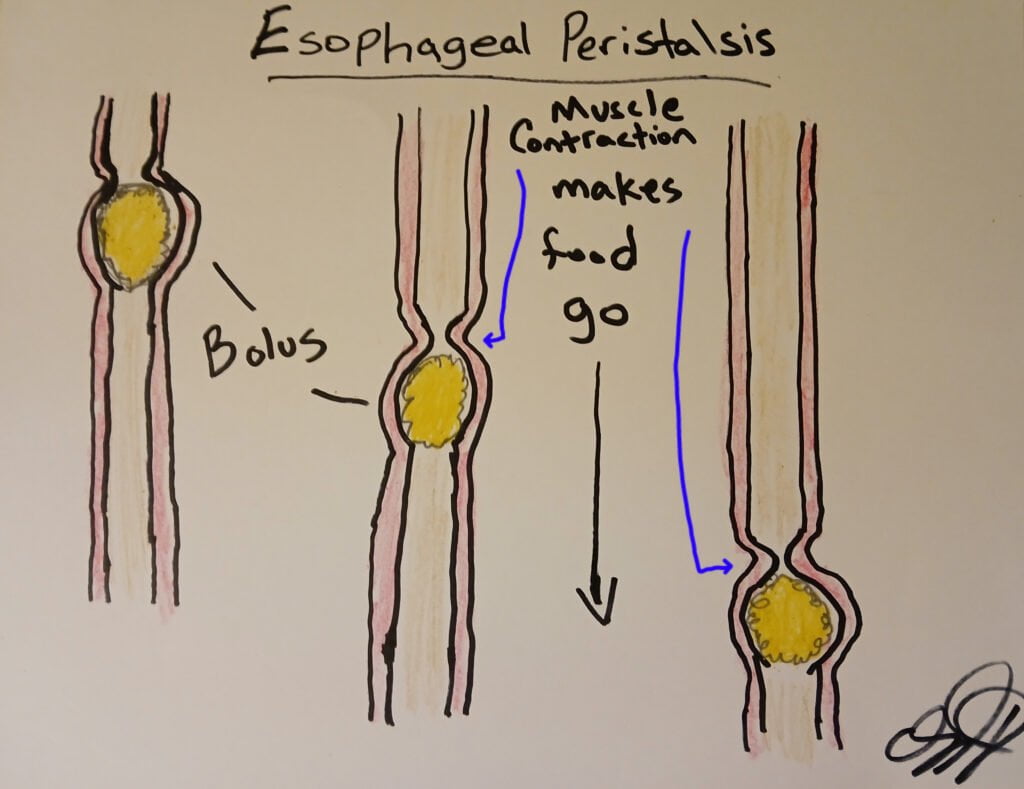

Next, peristalsis, which are wave-like muscle contractions, move the chyme through the digestive tract. In the small intestine, most of the nutrients are absorbed. The remaining waste moves to the large intestine, where water is absorbed, and finally, the waste is excreted.

A stainless-steel acupuncture pen and gua sha set for massage, reflexology, and tension relief.

View Product

View Product

When you eat, the process of chewing breaks down the food into smaller pieces. Saliva, which contains enzymes (amylase), mixes with the food, starting the process of digestion. This mixture of chewed food and saliva forms a soft mass called a bolus. The tongue then helps in pushing the bolus to the back of the mouth, initiating swallowing. From there, the bolus travels down the esophagus to the stomach.

To prevent food from entering the lungs, there’s a small flap of tissue called the epiglottis. During swallowing, the epiglottis closes over the windpipe (trachea) ensuring that the bolus goes down the esophagus and not into the lungs. It’s a crucial part of the swallowing mechanism for this reason.

From Bolus To Esophagus

Once the bolus is swallowed, it enters the esophagus. Here, peristalsis plays a crucial role. Peristalsis involves rhythmic, wave-like muscle contractions that move the bolus down the esophagus towards the stomach. These contractions are involuntary and ensure that the bolus keeps moving in the right direction, even if you’re lying down or standing up.

When the bolus reaches the end of the esophagus, a muscular valve called the lower esophageal sphincter opens to allow the bolus into the stomach. After entering the stomach, the bolus is further broken down by stomach acids and enzymes, transforming into chyme, which is then gradually released into the small intestine for nutrient absorption.

Break It Down Stomach, Break It down!

In the stomach, the food is broken down by gastric acid and enzymes. Gastric acid, primarily hydrochloric acid, creates a highly acidic environment. This acid helps in breaking down food and also kills bacteria that might have been ingested. The enzyme pepsin, which is activated by the acidic environment, begins the digestion of proteins.

Now, to protect the stomach lining from being digested by its own acid and enzymes, the stomach has several defenses. The most important is a thick layer of mucus that coats the stomach’s interior. This mucus barrier provides a protective layer, preventing the acid from damaging the stomach tissue. Additionally, the cells of the stomach lining quickly regenerate, further aiding in protection.

Common Conditions That Affect The Upper Digestive Tract

Common conditions associated with the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract include:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): A chronic condition where stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, causing heartburn and potential damage to the esophageal lining.2

- Peptic Ulcers: Sores that develop on the lining of the stomach, small intestine, or esophagus, often caused by Helicobacter pylori infection or long-term use of NSAIDs.

- Gastritis: Inflammation of the stomach lining, which can be acute or chronic, often caused by infection, alcohol use, certain medications, or autoimmune disorders.

- Hiatal Hernia: A condition where part of the stomach pushes up through the diaphragm into the chest cavity, which can contribute to GERD symptoms.

- Esophagitis: Inflammation of the esophagus, which can result from acid reflux, infections, medications, or allergies.

- Barrett’s Esophagus: A condition where the esophageal lining changes, often due to chronic GERD, increasing the risk of esophageal cancer.

- Esophageal Cancer: Cancer that forms in the tissues of the esophagus, with risk factors including smoking and heavy alcohol use13.

More Digestive System Resources

- National Institutes of Health. (2017) Your Digestive System & How it Works. Retrieved May 16th, 2024 – ↩︎

- Clarrett, D. (2018). Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Retrieved May 16th, 2024 ↩︎

- National Cancer Institute. (2021). Esophageal Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)–Patient Version

Retrieved May 16th, 2024 from https://www.cancer.gov/types/esophageal/patient/esophageal-prevention-pdq ↩︎

Jump-start your metabolism with the 21-Day Smoothie Diet! Replace meals with delicious, nutrient-packed smoothies that help burn fat, boost energy, and keep you feeling full. Start your transformation today →

Medical Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider with any questions about a medical condition or treatment.